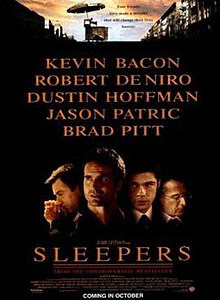

Sleepers (1996)

Throughout my life -- and probably through the centuries -- an ethical argument has moved around Christian circles: is it ever morally excusable to lie? Jesus said, “Let your ‘yes’ be ‘yes’ and your ‘no’ be ‘no,’” but aren’t there times when the right thing to do is tell a fib?

In these discussions, the name Rahab usually comes up. She was the prostitute who hid the Israelite spies in Jericho and lied when she was asked if she knew about their whereabouts.

Someone else brings up the Holocaust and says undoubtedly it would be fine to lie to Nazis about hiding Jews. And then someone will tell a story from The Hiding Place about Corrie ten Boom's family, who believed God had called them to hide Jews from the Nazis. With people hidden beneath a trapdoor under the kitchen table, one member of the family, when asked, said that yes, people were hidden under the table. Feeling foolish because they'd lifted the tablecloth to look under the table, the Nazis left without noticing the trapdoor under the rug. Whoever tells that story will remind the listeners that God will protect His people as they tell the truth.

Note: insert a smooth transition to this week’s Crime Movie, Sleepers here.

Written and directed by Barry Levinson, Sleepers is a very handy film for playing "Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon." The film stars not only Bacon as an abusive guard in a boys' reform school, but also features quite a number of other stars: Dustin Hoffman, Brad Pitt, Jason Patric, Billy Crudup, Minnie Driver, Bruno Kirby, Ron Eldard, and others. Most important (especially for our purposes here), Robert De Niro plays a priest, Robert “Bobby” Carrillo.

The film tells the story of four childhood friends living in Hell’s Kitchen in the 1960s: Shakes (Joe Perrino), Michael (Brad Renfro), John (Geoffrey Wigdor), and Tommy (Jonathan Tucker). All four are altar boys and also trouble makers. They have families that care for them -- with various levels of care. All four are cared for by their parish priest, Father Bobby. Shakes describes the priest in this way:

“Father Robert Carrillo was a longshoreman's son who was as comfortable sitting on a bar stool in a back alley saloon as he was standing at the altar during High Mass. He had toyed with a life of petty crime before finding his calling. He was a friend. A friend who just happened to be a priest.” Father Bobby plays basketball with the boys, but also calls them out when they start hanging out with neighborhood thugs.

One of the boys is beaten up by his mother’s boyfriend. After visiting the boy in the hospital, Father Bobby goes to see the boyfriend. He says to him, “You’re a big guy; how much do you weigh? How much do you think John weighs? Next time you will be fighting me. You won’t need a doctor, you’ll need a priest. See you in church.”

Someone else brings up the Holocaust and says undoubtedly it would be fine to lie to Nazis about hiding Jews. And then someone will tell a story from The Hiding Place about Corrie ten Boom's family, who believed God had called them to hide Jews from the Nazis. With people hidden beneath a trapdoor under the kitchen table, one member of the family, when asked, said that yes, people were hidden under the table. Feeling foolish because they'd lifted the tablecloth to look under the table, the Nazis left without noticing the trapdoor under the rug. Whoever tells that story will remind the listeners that God will protect His people as they tell the truth.

Note: insert a smooth transition to this week’s Crime Movie, Sleepers here.

Written and directed by Barry Levinson, Sleepers is a very handy film for playing "Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon." The film stars not only Bacon as an abusive guard in a boys' reform school, but also features quite a number of other stars: Dustin Hoffman, Brad Pitt, Jason Patric, Billy Crudup, Minnie Driver, Bruno Kirby, Ron Eldard, and others. Most important (especially for our purposes here), Robert De Niro plays a priest, Robert “Bobby” Carrillo.

The film tells the story of four childhood friends living in Hell’s Kitchen in the 1960s: Shakes (Joe Perrino), Michael (Brad Renfro), John (Geoffrey Wigdor), and Tommy (Jonathan Tucker). All four are altar boys and also trouble makers. They have families that care for them -- with various levels of care. All four are cared for by their parish priest, Father Bobby. Shakes describes the priest in this way:

“Father Robert Carrillo was a longshoreman's son who was as comfortable sitting on a bar stool in a back alley saloon as he was standing at the altar during High Mass. He had toyed with a life of petty crime before finding his calling. He was a friend. A friend who just happened to be a priest.” Father Bobby plays basketball with the boys, but also calls them out when they start hanging out with neighborhood thugs.

One of the boys is beaten up by his mother’s boyfriend. After visiting the boy in the hospital, Father Bobby goes to see the boyfriend. He says to him, “You’re a big guy; how much do you weigh? How much do you think John weighs? Next time you will be fighting me. You won’t need a doctor, you’ll need a priest. See you in church.”

Not exactly a meek and mild approach, but rather like a shepherd protecting a lamb from a wolf.

But one day the boys play a practical joke that goes awry, accidentally injuring an innocent bystander. They are sent to reform school. Before they leave, Father Bobby promises Shakes he’ll stay in touch. Shakes asks the priest to only send good news, even if bad things happen. “You asking me to lie?” the priest asks. Shakes tells him, sure. And the priest tells him he can’t do that.

At the reform school, the boys are verbally, physically, and sexually abused by the guards, particularly a guard named Nokes (Bacon).

Father Bobby visits Shakes at the reform school. Shakes, in a voiceover, says, “I loved Father Bobby, but I hated looking at him.” At this point, we've already seen Nokes sexually assault Shakes and mock him for his Mother Mary medallion. When Nokes rapes Shakes, he forces the boy to cry out to God, getting a perverse amusement out of mocking the boy’s faith.

Shakes says to Father Bobby, “You shouldn’t come here, I appreciate it and all, but it’s not the right thing to do.”

Father Bobby explains it was on his way, “I stopped off in Attica to see an old friend of mine.”

“You have friends in Attica?” Shakes asks.

“Not as many as I’d like,” Father Bobby tells him, “He’s a murderer. Best friend. We hung out together, like you and the guys. We were both sent up here. This place killed him. Made him. Made him not care anymore. Don’t let this place do that to you, Shakes.” The priest hugs the boy before he leaves, and Shakes says he never felt closer to another human being.

Shakes is released after a year, but the other boys serve another year after him. They grow apart over the years. Shakes (Patric) becomes a newspaper reporter and Michael (Pitt) becomes a lawyer working for the district attorney’s office. But Tommy (Crudup) and John (Eldard) become career criminals.

Years later, Tommy and John happen to meet their old guard, Nokes in a bar. They talk to him until Nokes realizes who they are. They then shoot him dead in the dark back room of the bar.

Tommy and John are arrested, and Michael insists on taking the case. Michael discloses to Shakes he took the case just to get his friends acquitted. He has a plan to make this happen, but a key part of his plan is bringing in Father Bobby to commit perjury and say he was with Tommy and John when the murder was committed.

This brings us back to the beginning of this post and the question, “Is it ever right to lie?” I won’t do any spoilers here about what Father Bobby does in the courtroom. I’ll just say that through most of the film, I thought I’d give the priest a Movie Churches rating of Four Steeples, but in the end, I’m just giving him Three Steeples.

But one day the boys play a practical joke that goes awry, accidentally injuring an innocent bystander. They are sent to reform school. Before they leave, Father Bobby promises Shakes he’ll stay in touch. Shakes asks the priest to only send good news, even if bad things happen. “You asking me to lie?” the priest asks. Shakes tells him, sure. And the priest tells him he can’t do that.

At the reform school, the boys are verbally, physically, and sexually abused by the guards, particularly a guard named Nokes (Bacon).

Father Bobby visits Shakes at the reform school. Shakes, in a voiceover, says, “I loved Father Bobby, but I hated looking at him.” At this point, we've already seen Nokes sexually assault Shakes and mock him for his Mother Mary medallion. When Nokes rapes Shakes, he forces the boy to cry out to God, getting a perverse amusement out of mocking the boy’s faith.

Shakes says to Father Bobby, “You shouldn’t come here, I appreciate it and all, but it’s not the right thing to do.”

Father Bobby explains it was on his way, “I stopped off in Attica to see an old friend of mine.”

“You have friends in Attica?” Shakes asks.

“Not as many as I’d like,” Father Bobby tells him, “He’s a murderer. Best friend. We hung out together, like you and the guys. We were both sent up here. This place killed him. Made him. Made him not care anymore. Don’t let this place do that to you, Shakes.” The priest hugs the boy before he leaves, and Shakes says he never felt closer to another human being.

Shakes is released after a year, but the other boys serve another year after him. They grow apart over the years. Shakes (Patric) becomes a newspaper reporter and Michael (Pitt) becomes a lawyer working for the district attorney’s office. But Tommy (Crudup) and John (Eldard) become career criminals.

Years later, Tommy and John happen to meet their old guard, Nokes in a bar. They talk to him until Nokes realizes who they are. They then shoot him dead in the dark back room of the bar.

Tommy and John are arrested, and Michael insists on taking the case. Michael discloses to Shakes he took the case just to get his friends acquitted. He has a plan to make this happen, but a key part of his plan is bringing in Father Bobby to commit perjury and say he was with Tommy and John when the murder was committed.

This brings us back to the beginning of this post and the question, “Is it ever right to lie?” I won’t do any spoilers here about what Father Bobby does in the courtroom. I’ll just say that through most of the film, I thought I’d give the priest a Movie Churches rating of Four Steeples, but in the end, I’m just giving him Three Steeples.