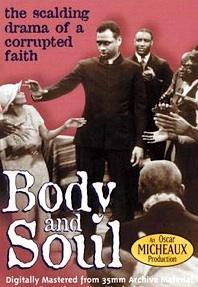

Red Hook Summer (2012)

By almost any criteria, Spike Lee is the most successful African American filmmaker, past or present. Financially, he's made films in the $100 million dollar club. His films have won Oscars, BAFTAs, Peabodys, and the Cannes Grand Prix. He’s won Emmys for his work in television. Four of his films have been chosen for preservation by the Library of Congress in the National Film Registry. His production company (40 Acres and a Mule) has made dozens of films, and since he’s acted in many of his films and in many TV commercials (often with Michael Jordan), he’s widely known in popular culture. Most importantly for this blog, he's made movies with ministers and churches -- such as 2012’s Red Hook Summer.

The film is about a young teen named Flik (Jules Brown) who comes from Atlanta to Brooklyn to spend the summer with a grandfather he's never met. Flik brings his computer tablet with him and uses it to film the world around him. Since Lee himself grew up in Atlanta and his family moved to Brooklyn, it's not hard to imagine that the writer/director saw himself in the character. “Flik” is not too far removed from “Spike” as a nickname.

Flik's grandfather is a minister, “Da Good Bishop Enoch Rouse” (Clarke Peters). There's a Jesus fish on the front door, an “I ‘Heart’ Jesus” magnet on the fridge, and no TV set in the house. The latter concerns Flik greatly. Flik learns he will be spending most of his summer at the “Lil’ Peace of Heaven Baptist Church of Red Hook” where his grandfather is the pastor.

At the church, Flik meets Deacon Zee (Thomas Jefferson Byrd) who also serves as janitor of the church. Zee doesn’t hide his love for the bottle or his concerns about the financial solvency of the church, telling the pastor in Flik’s presence, “We owe $6000 on last year’s heating bill, the church van is broke again, the roof is about to go and the plumbing down here would give the Roto-Rooter man the mumps.” Bishop Rouse assures the deacon that God has shown him in a dream that a big donor will be coming their way to deal with the church’s financial troubles.

Flik also meets a girl his age named Chazz Morningstar (Toni Lysaith), whose company makes life at his grandfather’s much more tolerable. Besides that, his grandfather assures him that the neighborhood will be good for him, “Red Hook is a window to the world, there is no better place to see God’s creation.”

Enoch preaches both about societal problems and about Jesus. He preaches against teen pregnancy and rap music, but he also preaches about the hope found in Jesus. His congregation and the community do seem to have confidence in him.

Until one day when a strange man comes into the church in the middle of a service. The pastor hopes it is the man from his dream with a big check to save the church from its financial woes, but it’s not. This man knew the pastor years before. When the man was a young boy, Enoch sexually abused him. The man makes those accusations before the congregation.

The pastor admits it is all true. His previous congregation had given money to the family of the boy he molested to cover it all up, and Enoch then left that congregation in the south and came to Brooklyn.

Upon learning about this, the congregation in Brooklyn turns against him. They allow thugs in the neighborhood to beat the pastor up, and Flik returns to his parents in Atlanta.

It's not hard for people to understand Box (Nate Parker), the young thug in the film who beats up the pastor. Many people find murder more understandable and forgivable than the sexual abuse of minors. It's one of the most heart-wrenching problems in the Church.

This abuse of power has been one of the greatest sources of harm I've seen in the church. Many have left the church because of such abuses. It is difficult to see such abusers as being worthy of life, let alone redemption.

It's not hard for people to understand Box (Nate Parker), the young thug in the film who beats up the pastor. Many people find murder more understandable and forgivable than the sexual abuse of minors. It's one of the most heart-wrenching problems in the Church.

This abuse of power has been one of the greatest sources of harm I've seen in the church. Many have left the church because of such abuses. It is difficult to see such abusers as being worthy of life, let alone redemption.

I’ve come to look at things a little differently in my current job. The mission where I work is one of the few recovery programs in the area that takes sexual offenders. These men were abused themselves, usually when they were young. Many of them have still done very horrible things.

I believe these men deserve a chance at redemption because my understanding of Scripture is that Jesus died for everyone (II Cor. 5:15). It is God’s desire that all should know His grace -- but not everyone should have a place of leadership in a church. I Timothy 2 gives a list of qualifications for leadership that includes such qualities as being “above reproach… temperate… self-controlled… not violent but gentle…” Not everyone is called to leadership in the church or to the pastorate. Those who commit certain sins and acts should never be allowed to take certain roles of responsibility in the church. The Good Doctor Bishop Enoch Rouse should never have taken a role as pastor again.

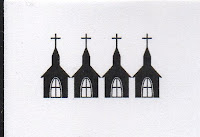

Therefore, Rouse receives our lowest Movie Churches rating of One Steeple.

One last note about this film. Spike Lee not only wrote and directed this film; he also plays a role. He plays Mookie, a pizza delivery man -- the same role he played in 1989’s Do the Right Thing. For those who have seen that film, he still works for Sal.

I believe these men deserve a chance at redemption because my understanding of Scripture is that Jesus died for everyone (II Cor. 5:15). It is God’s desire that all should know His grace -- but not everyone should have a place of leadership in a church. I Timothy 2 gives a list of qualifications for leadership that includes such qualities as being “above reproach… temperate… self-controlled… not violent but gentle…” Not everyone is called to leadership in the church or to the pastorate. Those who commit certain sins and acts should never be allowed to take certain roles of responsibility in the church. The Good Doctor Bishop Enoch Rouse should never have taken a role as pastor again.

Therefore, Rouse receives our lowest Movie Churches rating of One Steeple.

One last note about this film. Spike Lee not only wrote and directed this film; he also plays a role. He plays Mookie, a pizza delivery man -- the same role he played in 1989’s Do the Right Thing. For those who have seen that film, he still works for Sal.